Standing in my ex-wife’s kitchen, talking with relatives, I thought to myself how we hadn’t all been together as a family in 20 years. There was a time when we had been close. Two brothers, two sisters, three children, and 14 nieces and nephews. At one time this had been my tribe.

In most cases, family is never not family but, as time passes, family is sometimes supplanted by surrogates. Ultimately we choose whether to adopt and to be adopted by others based on circumstance rather than blood. All of us but one left the sleepy berg of Mineral Wells and, in a functional sense, lost track of each other. We haphazardly kept in touch by phone on holidays and sporadically by social media. In the process, we each adopted surrogates who filled the gap.

In most cases, family is never not family but, as time passes, family is sometimes supplanted by surrogates. Ultimately we choose whether to adopt and to be adopted by others based on circumstance rather than blood. All of us but one left the sleepy berg of Mineral Wells and, in a functional sense, lost track of each other. We haphazardly kept in touch by phone on holidays and sporadically by social media. In the process, we each adopted surrogates who filled the gap.

I recall a moment many years prior when my former wife and I were asking our three kids how they wanted to spend a particular Sunday afternoon as the weekend was drawing to a close. Only Tim weighed in with a reply.

“I want to have dinner and spend time with family.”

From the earliest moment, it seemed, he valued time with family more than anything else and he, more than any of us, valued that time above all else. Perhaps that’s not entirely true, but it’s how I recall him and—as such—I thought of him that day.

I thought of how he would have loved this family gathering—this reunion as it were.

Not all were present that day but most made an appearance, an occasion made possible by the confluence of a wedding on a Saturday and a birthday on a Sunday. Events that point to a sense of life. It stood in stark contrast to the loss, still fresh in my mind from 18 months earlier.

“Would you like to see his room?”

I turned to see my former wife earnestly looking at me, a sense of anxiety visible in her eyes.

“I left it just as it was the day he left us.”

“Sure.” I replied.

She turned and walked out of the kitchen; I followed her. I made my way behind her, feeling as though I were a death row prisoner taking the final walk to the dreaded room, the iconic chamber that to my ex-wife represented life, but to me represented its absence. To her it was a way to keep his memory alive. To me it was a hollow shell, a lifeless corpse that represented the absence of the child his mother and I made together.

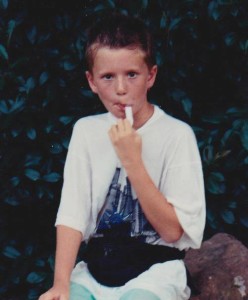

I entered the room with trepidation and glanced at the décor. I don’t recall any meaningful detail. Only sports memorabilia from the University of Texas and the Dallas Cowboys—nothing more, except one thing. There was a portrait of him, an image I’d seen countless times. I’m unable to recall much of anything else in that moment with any real clarity other than the emotion, a thing that shuns language. Words fail to describe the intense range of emotions in such a circumstance, like light split by a prism.

Love, anger, joy, sadness and the myriad of hues in between each feeling. I can only really remember what I felt—and what I felt was loss. I turned to his mother and simply said “We made beautiful babies.”

“Yes.” came her reply. And in that moment I was reminded of the time before trouble. Before the addiction. I remembered the child who was transitioning out of childhood so many years ago.

I was sitting at the kitchen table having a cup of coffee. I looked out the window into the backyard. Tim and his sister, Rachel, our second child, were sitting on the patio talking. They were nine and eight and it was the first time I’d ever witnessed anything akin to a conversation between my children that didn’t involve play.

It was one of those moments all parents eventually experience: the beginning of the end of parenthood. You have another decade or so—but you can see the sunset of childhood on the horizon. There was still some time. He was still innocent, an unassuming child who simply loved his family just like most kids his age. And despite the changes I had witnessed, which pointed to something foreboding, there was still time to spend with him—with each of them.

And in that moment as I sat in his room looking at his mother and the shrine she had dedicated to him, and thinking of that nine year old child, I could only think with a deep aching regret the time I missed. I sold the time I could have spent with my children for a paycheck.

It’s a cliché born of life experience from people my current age I heard countless times in my twenties: “One day you’re going to miss this. They’re little like this for a just a little while. You’re going to look back and regret the 90 minute commute and the time spent in someone else’s office working for a virtual stranger.” And then I would dismiss that thought with the notion that “Then I won’t have to worry about feeding, clothing and housing five people on a substandard salary.”

So with the advantage of a retrospective view, what would I have changed? The honest truth is, nothing. We are sometimes forced to make choices and the choice I was forced to make in that circumstance was to work long hours to provide for my family—just like almost every other parent. But that reality? It diminishes the regret not one bit, and the regret is underscored when a child’s life is cut short.

In such moments you needlessly and pointlessly kick yourself for not being there enough and for not being fully present when you are there. You remember bringing the problems of work home with you and trying to listen to your wife as she talks about the trials of the day. You try to steal a moment as your children explain to you things that are important to them but which often make very little sense to you. You try to attend to everything that demands your attention the moment you walk through the door, and you’re dead on your feet and there is no rest.

And you remember that reality as it was. Not romantically. Not Idyllically. You remember—almost feel the travail. But then you take a deep breath and wish that you could trade every day from that to this for one more day with your child.

One more day.

I have repeated it more times than I can count. Just one more day, God. Could I not have just one more day?

The answer is, of course, no. So instead you try to recall some memory. Some situation. The color and shape of his eyes. The shape of his face. The color and cut of his hair. The slight build of his frame, and the tenderness of his words before it all began to come apart at the seams.

My memory was a quiet conversation I witnessed between Tim and his sister, Rachel, while drinking a cup of coffee on a Saturday morning…