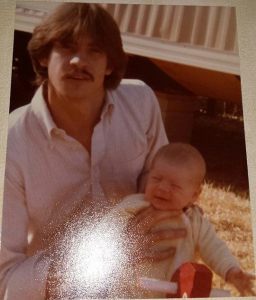

It was strangely warm and humid that winter day. The pretty, 20 year-old girl with brown hair and matching eyes looked as though she might burst from the life kicking inside her. She occupied herself with chores around the humble mobile home that was our abode in the tiny hamlet of Mineral Wells, Texas.

The date was January 15th 1982, and there was hope. Hope and optimism were ever present on that unusually warm winter day.

And we waited.

A warm meal, a night of television, and a warm blanket filled the time as we noticed a sudden shift in the temperature. This is a common phenomenon in Texas. It’s not unusual for the weather to turn on a dime. An undeniable maxim in Texas is that if the weather is balmy in winter, a glacial freeze is coming—and come it did.

That night ushered in a cold front dubbed the Siberian Express, a record breaking Blue Norther that sent temperatures plummeting across the Midwest and into Texas. And with it came the new life: our first born, Timothy Evans Oliver.

His first night outside the warmth and protection of his mother’s womb, the temperature was a chillingly raw 15 degrees. Looking back, it now seems like an omen. A child born to lower middle-class parents, who would know difficulty most of his life, but one who would also eventually overcome life’s adversity.

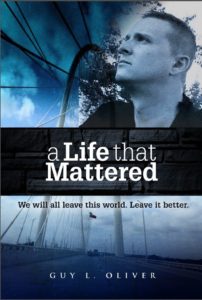

It is this tension of strained adversity and the unending struggle to overcome it that built the frame of notability that characterizes his story. It is a story of redemption although it ends so uncharacteristic of most redemptive stories. And it is that uncharacteristic ending that makes his story worth telling because it was only after witnessing the end, that we could step back and understand precisely what had been wrought.

The frame was decorated with a fabric containing patterns so heart wrenching in the making, yet so uplifting when we were able to retreat a few paces and witness his life in its entirety.

Most redemptive stories end with something akin to “And they all lived happily ever after.”—but in a few, the protagonist does not survive and the supporting characters must go on without him. They must go on living and in so doing they must find meaning in the gain of the life they knew with him and the loss of his departure. For this is where true redemption lies. It is hidden in the understanding of the protagonist in the aftermath of his demise.

We do not live perfect lives but when our lives are complete, those we leave behind begin, little by little, to understand the redemption of all our mistakes and shortcomings through the gift of our existence.

The life Tim lived is just such a story.

To the world at large, Tim is seen as a ne’er-do-well. A common meth addict with seven felony convictions. A low-life thief who stole from his own family and refused to work for a living. A thing to be discarded on the heap of our so-called justice system. That unforgiving lens is how we justify our treatment of these people as refuse. I know the lens well; I once wore those spectacles.

Long before his passing I said on several occasions that “If he were anyone else’s son, I would say ‘Lock him up and throw away the key.’ But he isn’t someone else’s son. He’s my son.”

In a moment of reflection in the wake of Tim’s passing, I lamented to a friend about the throw-away attitude of our society regarding our prisoners, our addicts, and our mentally infirm. Her reply was that of a mother:

“When I see someone abused in the name of justice, I always think ‘That’s someone’s baby. Someone rocked that person as a child. That person mattered to someone.’ “

Tim did matter. But he mattered not simply because he was my son. He mattered because of what he was capable of and all the lost potential of what could be. We all witnessed the tender heart that compelled him to do anything in his power for anyone in need. The moments of lucidity and clarity when the veil of drug induced madness would be lifted, albeit less frequently and more briefly as time passed, reminded us of the person Tim actually was.

We were fondly reminded in those moments of the little boy with the big heart, the misguided teen who lost his way, and the grown man who ultimately mattered, and this is his story.

And although it is a story of redemption, it is also a story of destruction, for there can be no redemption without destruction. In the wake of his passing I have spent countless hours recounting the good and the bad, the vice and virtue, the purity and depravity not only of his life, but of my own.

The unexpected death of a loved one, especially that of a child, demands self-examination. You aren’t given the option of ignoring your contribution to such an event. You are forced to look at yourself and the way you have conducted your life with respect to such an event. You are compelled to ask questions theretofore unconsidered.

And while the questions are innumerable, the answers are unforthcoming. What materializes instead is the realization that, ultimately, you are mortal. Finite. Human. Ultimately, you realize you have very little control over the outcome of such a thing as the untimely end of a life. Yet you examine your role, and this reality compounds the perplexity that asserts itself as you endlessly search for answers.

In the case of Tim’s passing we were all forced to allow acceptance to subsume unanswerable questions, and I suspect that is the norm for any such loss.

I have a friend who some time ago had to put down a dog she had raised from a puppy. I listened as she described the experience of going through the decision process of actively ending the life of her beloved companion. The highest hurdle she was forced to traverse was the notion of playing God, and I think that aspect was the most difficult because we aren’t meant to play God. Irony being what it is, though, not being able to play God is the most difficult aspect of unexpectedly losing a loved one. We are left with a sense of injustice and absence of control.

We want to play God. We want to bring back the deceased or miraculously prevent the circumstance that ended their existence here with us. Yet we know we are powerless to do so, and madness often ensues. A kind of knowing in a sea of disbelief that the event has befallen us.

Ultimately, the mind of the bereaved creates a story around that person and his life. What it meant, why it mattered, and who it touched.

“Strange, isn’t it? Each man’s life touches so many other lives. When he isn’t around he leaves an awful hole, doesn’t he?”

This over-quoted line from It’s a Wonderful Life is eloquent in both its brevity and meaning. How many lives did Tim touch in a meaningful way? We cannot know, but in attempting to achieve that understanding we overlook a more important question. In the horrible aftermath of losing a loved one, we should also ask, “How many lives have I touched?” For we are still among the living.

Our mission should be to matter to everyone in our lives, and tragic events such as losing a loved one, should underscore the importance of every life, not just that of the deceased. You matter. You matter because of the opportunity your life represents and the people you touch every day…